Queers Rush In (Part 1)

How two lesbians rebelled against feminism

“I am not a believer in ‘facts’ unmediated by cultural structures of understanding.”

– Gayle Rubin (1992)

“Who devises the protocols of ‘clarity’ and whose interests do they serve?”

– Judith Butler (1999)

In the 1980s, a rising generation of female scholars felt alienated by feminism. They didn’t see all men as avatars of the patriarchy – some were their comrades in oppression as “sexual minorities.” Writing in a pretentious style imported from Paris, their essays valorized sexy gay guys while scoffing at “facts” and “truth.” The project became known as queer theory.

Many critics of trans ideology think it grew out of queer theory, particularly Judith Butler’s 1990 book Gender Trouble. This is wrong. The rationale for gender medicine comes almost entirely from Harry Benjamin, an endocrinologist who published his opus in 1966. Butler didn’t turn her attention to transgenderism until the late 1990s; other foundational queer theorists never focused on it. Doctors and lawyers draw on a long line of pseudoscience, not literary theory, to justify transing kids.

Queer theory and trans ideology are not the same thing, neither spawned the other, and they are not fully aligned. But queer theory became a vessel for trans ideology, ferrying it through parts of society that defer to English professors, because it loves sex-related rebellion, sophistry, and books about “gender” that don’t say what gender is.

In this three-part essay I’ll explore queer theory’s role in building the trans utopia we enjoy today. Today’s entry, Part 1, introduces America’s founding queers: anthropologist Gayle Rubin and philosopher Judith Butler.

I’ll be tracking three movements. First, a type of gay intellectualism that revels in subversion. (This will become known as queer theory.) Second, “radical” feminism which is intensely vigilant against threats to women. The subversive gays and radical feminists are adversaries. Third, trans ideology. It’s aloof from the gays and feminists – for now.

Feminism in 1984

The feminist movement of the 1970s was fueled by grassroots energy, cultural momentum, and philanthropy. The most significant source of funding was the Ford Foundation, but other big guns – Rockefeller, Carnegie, Mellon – also backed everything from nonprofit law firms to painters. On campus, Ford seeded “women’s research centers.” The vibe was optimistic as women rapidly secured new freedoms.

In 1976, the Rolling Stones promoted its new album, Black and Blue, with a Sunset Boulevard billboard that showed a woman tied up and covered in bruises. The caption: “I’m ‘Black and Blue’ from the Rolling Stones – and I love it.” The offensive ad galvanized women to speak out against gross media images.

This turned into an activist campaign against the public degradation of women and then, following some mission creep, to a war on porn. With high-profile spokeswomen like Gloria Steinem, an endorsement from the National Organization for Women, and links to NYC power brokers (who wanted to clean up Times Square), by 1980 the movement had momentum.

But it never gained institutional backing. When Barnard College hosted a conference on sexuality in 1982 – funded by a grant from the Helena Rubinstein Foundation and ticket sales to the general public – it platformed pro-porn perspectives but not anti-. The latter camp leafletted and pelted presenters with hostile questions.

Anti-porn “radical feminists” had two vaunted leaders: Andrea Dworkin and Catharine MacKinnon. Dworkin was indie, living off her writing and speaking. Legal scholar MacKinnon was respected but couldn’t get a job. America’s top law schools gave her one “visiting” gig after another, but never a tenure-track position. (Finally the University of Michigan hired her with tenure in 1990.)

Dworkin and MacKinnon were sharp. No matter where you stand, it’s fun to read their work and argue about them, and their polemics seem prescient as young people today accuse internet porn of ruining sex and worse. But lesser radical feminists of the 1980s could be vexatious. Some promoted “political lesbianism” (shunning men despite feeling attracted to them) while attacking real lesbians for adopting masculine styles. You can see why a left-leaning college girl would shop around for another vision of feminism.

Financial support for feminism was shifting. A 2007 study found that philanthropists of the 1970s favored broad efforts to expand women’s horizons in employment and education. In the 1980s, perhaps antsy after the low-hanging fruit was picked, they bent toward serving downtrodden women. Grant-chasers defined their clients as mentally ill, homeless, drug addicted, and victims of violence. In 1985, a trickle of funding appeared for lesbians. Foundations and universities began backing “feminist” scholars who were writing on gay people (or were perceived to be). The women’s movement became more fragmented.

The rich didn’t fully control the shape of feminism in the 1980s. Everyday women influenced it by buying tickets to lectures on sexuality, volunteering for anti-porn actions, shopping at feminist bookstores … and choosing schools based on sex-related course offerings.

Transsexualism in 1984

The movement for “sex reassignment surgery” ran aground in 1979, after Johns Hopkins U announced the practice didn’t help patients. At the same time, the sponsor of its propaganda arm, Reed Erickson, sank into drug addiction. Transsexuality faded from public view.

The word “transgenderist” was introduced in the 1970s by Virginia Prince to describe fetishists like himself who used estrogen to grow breasts but spurned genital surgery. By 1991 his ilk decided to run with “transgender” for their nascent civil rights movement, noting that the word had already been in use a while. It probably did not spread far beyond this niche community before 1991; “transsexual” was still proper terminology in the 80s.

Gayle Rubin, b. 1949 (Anthropology)

As a UMich anthropology grad student in 1975, Gayle Rubin published “The Traffic in Women: Notes on the ‘Political Economy’ of Sex.” It analyzed “women’s oppression” through the lens of Marx and others, arguing it was socially constructed. This established her as a promising feminist.

Rubin, who’d come out as a lesbian years earlier, moved to San Francisco in 1978 to conduct ethnography on the local gay male leather scene. In a 1994 interview she’d explain to Judith Butler what intrigued her:

“Most of the actual practice of gay male culture was objectionable to many feminists, who mercilessly condemned drag and cross-dressing, gay public sex, gay male promiscuity, gay male masculinity, gay leather, gay fist-fucking, gay cruising, and just about everything else gay men did. I could not accept the usual lines about why all this stuff was terrible and anti-feminist, and thought they were frequently an expression of reconstituted homophobia. By the late 1970s, there was an emerging body of gay male political writing on issues of gay male sexual practice. I found this literature fascinating, and thought it was not only helpful in thinking about gay male sexuality, but also that it had implications for the politics of lesbian sexual practice as well.”

Soon after moving to San Francisco she formed Samois with Pat Califia and others, which they described as a lesbian-feminist “SM” (sadomasochist) organization. So began a grinding conflict – Rubin compared it to “gang warfare” – with the local anti-porn feminists over whether violence against women was inherently bad for women.

The lesbians of Samois didn’t just troll straight women who wished they were lesbians. They also discussed boundaries, exchanged consent, cared for one another after (staged) traumas, nested (in a dungeon), and shopped. From the 1994 interview:

“I do not see how one can talk about fetishism, or sadomasochism, without thinking about the production of rubber, the techniques and gear used for controlling and riding horses, the high polished gleam of military footwear, the history of silk stockings, the cold authoritative qualities of medical equipment, or the allure of motorcycles … [H]ow can we think of fetishism without … the seductions of department store counters, piled high with desirable and glamorous goods?”

Rubin discovered these baubles because she was sniffing around a movement that I’ll call gay nihilism. Mainstream gay activism had sought assimilation since the 1950s, when the Mattachine Society and Daughters of Bilitis formed. But the sexual revolution of the late 1960s gave voice to an edgier type of gay. They said they were not the same as straights. In fact, they said, homosexuals were really more like pedophiles.

Organized pedophiles had a foothold in their movement. Even today, some gay historians, backed by “LGBTQ” grants, write wistfully about the North American Man-Boy Love Association (NAMBLA) as representing “radical queer inclusivity.”

In 1982, at that controversial Barnard conference, Rubin set forth a new framework for discussing sexuality. She finalized it two years later.

“Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality” (1984)

Rubin kicks off with an epigraph from a 19th century French doctor about how to stop “little girls” from touching themselves by “burning the clitoris with a hot iron.”

You don’t want to be like that guy, right? Rubin introduces us to the alternative: “recognizing the sexuality of the young, and attempting to provide for it in a caring and responsible manner” by tearing down “law devoted to protecting young people from premature exposure to sexuality[.]”

Rubin doesn’t go there immediately. First she proclaims that society has “become dangerously crazy about sexuality” – we’re caught up in a “moral panic” about homosexuality, public sex, porn, and “sex offenders.” She puts forward a sweeping historical argument that crackdowns on porn and prostitution go hand in hand with harassing gay people. If true, this would suggest gay people and pimps have shared interests. But she doesn’t quite have the goods:

“Although anti-homosexual crusades are the best-documented examples of erotic repression in the 1950s, future research should reveal similar patterns of increased harassment against pornographic materials, prostitutes, and erotic deviants of all sorts.”

“For over a century,” Rubin continues, “no tactic for stirring up erotic hysteria has been as reliable as the appeal to protect children.” She decries recent media coverage about a “vice ring organized to lure young boys into prostitution and pornography.” She doesn’t show that the reporting is false. (Boy prostitution is a problem.)

Rubin expresses gratitude toward the ACLU and NAMBLA for opposing recent child porn bills.

Rubin relates the tale of an art professor, Jacqueline Livingston, fired by Cornell for showing students photos of “her seven-year-old son masturbating.” After bemoaning the “harassment and anxiety” Livingston suffered “for her efforts to capture on film the uncensored male body at different stages,” Rubin argues that “it is easy to see someone like Livingston as a victim of the child porn wars. It is harder for most people to sympathize with actual boy-lovers … Consequently, the police have feasted on them.”1

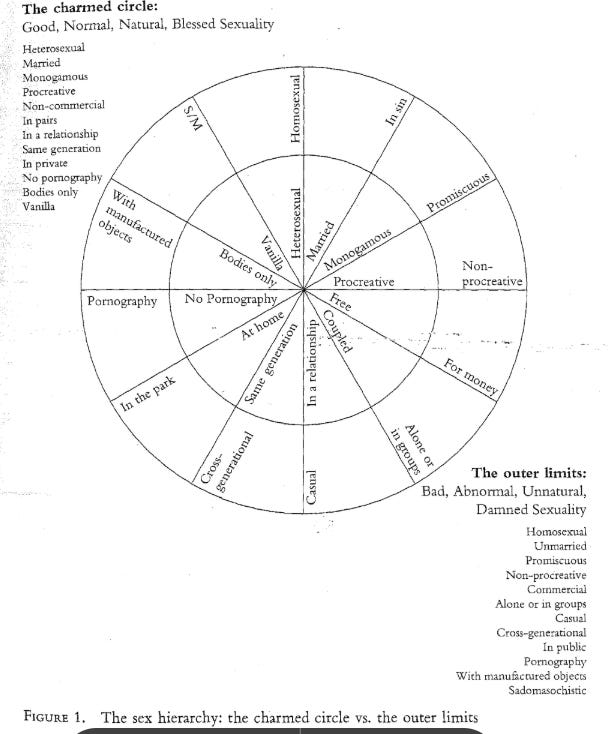

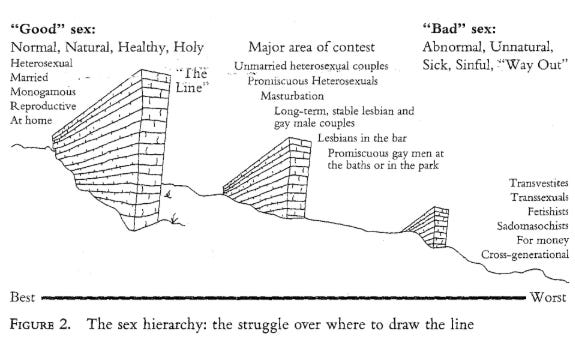

Thinking Sex is most famous for its formulation of a sexual hierarchy of privilege, which it represents using two diagrams – a “charmed circle” and a row of brick walls in a meadow. See if you can spot NAMBLA hiding in each like Waldo.

Rubin places “Long-term, stable lesbian and gay male couples” in the middle of the field – less oppressed than slutty gays, transsexuals, and “generation” fetishists. Later she witheringly describes gay couples as “verging on respectability.”

Rubin unpacks the data:

“All these models assume a domino theory of sexual peril. The line appears to stand between sexual order and chaos. It expresses the fear that if anything is permitted to cross this erotic DMZ, the barrier against scary sex will crumble and something unspeakable will skitter across.”

Rubin created the models herself, so their assumptions are hers. Does she think acceptance of gay couples will open the door to pedophilia? She seems to be using the word “assume” just to get around providing evidence for the “domino” idea that gays and pedophiles stand and fall together.

Rubin doesn’t directly engage arguments that hitting on children, legalizing whipping, turning sex into a business, or opening up public parks for orgies cause harm. Here’s the closest she comes:

“This kind of [hierarchical] sexual morality has more in common with ideologies of racism than with true ethics. It grants virtue to the dominant groups, and relegates vice to the underprivileged. A democratic morality should judge sexual acts by the way partners treat one another, the level of mutual consideration, the presence or absence of coercion, and the quantity and quality of the pleasures they provide.”

Nevermind that some men in 1984 were having sex “in the park” – a fount of HIV – because they had wives and kids at home.

Rubin envisions new frontiers in employment law:

“Sadomasochists leave their fetish clothes at home, and know that they must be especially careful to conceal their real identities. An exposed pedophile would probably be stoned out of the office. Having to maintain such absolute secrecy is a considerable burden. Even those who are content to be secretive [because they have a tiptoeing fetish] may be exposed by some accidental event.”

Rubin vs. Feminists

Rubin casts anti-porn feminists as conservative. She refers to “right, left, or center” feminist positions on sexuality after complaining that anti-porn feminist rhetoric is inspiring the Pope and the “right wing.”

Ultimately, she “want[s] to challenge the assumption that feminism is or should be the privileged site of a theory of sexuality.” She’s trying to make something new. But she still views the whole world in terms of oppression. “[L]esbian feminist ideology has mostly analyzed the oppression of lesbians in terms of the oppression of women. However, lesbians are also oppressed as queers and perverts[.]”

In 1994, Rubin reflects:

“I looked at sex ‘deviants,’ and frankly they didn’t strike me as the apotheosis of patriarchy. On the contrary, they seemed like people with a whole set of problems of their own, generated by a dominant system of sexual politics that treated them very badly.”

Rubin wants to transcend 1980s feminism but she keeps following the first rule of 1980s feminism: identify the apotheosis of patriarchy.

Corrupting the Lesbians

Rubin conjures a malign System that will come for you next (emphasis added):

“There is systematic mistreatment of individuals and communities on the basis of erotic taste or behavior. … Specific populations bear the brunt of the current system of erotic power, but their persecution upholds a system that affects everyone.”

How does Rubin know the System that oppresses pedophiles, johns, and tree-humpers is the same System that (in 1984) disallows gay marriage? Is it because both Systems involve statutes? Is it because all this stuff appears together in the Charmed Circle that Rubin drew? Recall that she can’t prove correlation between anti-gay oppression and other types, nevermind causation.

Technically Rubin is calling out to “everyone.” But the demographic most likely to read this essay and take it seriously — the college students who enrolled in women’s studies to talk about sexuality — are young lesbians.

Rubin is prodding these malleable readers to swear off the “respectable” world to defend sadists who whip 13-year olds in the park (consensually). Of course this is a bad idea; of course their prospects will fall, not rise, if they mount such a defense. You can tell Rubin held little sway for years because otherwise gay people never would have won the right to marry and raise children.

But Thinking Sex planted some seeds that came to flower in the 2010s.

A Glimpse of Trans

Thinking Sex refers to “transsexuals” and “transvestites” only in passing. This reminds me of Mary Dunlap’s 1979 essay, which mentions transsexuals as fellow victims but doesn’t seem tapped into their movement.

The text never utters “transgender” except in a footnote that was added to the 1992 reissue. The bracketed language is my clarification:

“Throughout this essay I treated transgender behavior and individuals in terms of the sex system [sexual behavior] rather than the gender system [man/woman], although transvestites and transsexuals are clearly transgressing gender boundaries. I did so because transgendered people are stigmatized, harassed, persecuted, and generally treated like sex ‘deviants’ and perverts. … ”

The reason she finesses her past choice to link trans people with sexuality is probably that she got the memo — trans activists bitterly deny the link.

Judith Butler, b. 1956 (Philosophy)

“The only way to describe me in my younger years,” Judith Butler says, “was as a bar dyke who spent her days reading Hegel and her evenings, well, at the gay bar.” But she sometimes chafed at the culture. “I entered into a lesbian community in college—late college, graduate school—and the first thing they asked was, ‘Are you a feminist, are you not a feminist?’ ‘Are you a lesbian, are you not a lesbian?’ and I thought, ‘Enough with the separatism!’”

In the porn wars, Butler at first sided with radical feminists. But as she followed the debate, she changed her mind.

The day after Barnard’s fateful 1982 conference on sexuality, the Lesbian Sex Mafia held a “speakout on politically incorrect sexuality” in Greenwich Village. Butler, then a grad student in philosophy at Yale, appeared as one of six invited speakers. She’d been “emboldened” by reading the work of the Barnard headliners, including Rubin.

Historian Rachel Corbman recounts Butler’s “nice Jewish lesbian tale” about her uncle who was institutionalized after repeatedly flashing his malformed genitals:

“Butler interprets her uncle’s proclivity for exposing himself in public restrooms as a ‘profound and important . . . act of resistance’ designed to ‘transfigure the meaning of gender’ by claiming ‘this new gender as his own.’ In the closing moments of her remarks she then draws a direct link from her absent uncle to his three ‘very, very gay’ nieces and nephews, including herself. ‘He turned to the world in an act of defiance and asked them to look at the ambiguity they sought to suppress. He didn’t know then that there would be more of us, testing the limits of gender. Perhaps if he had known he would have realized that he lacked nothing.’”

In 1999, Butler would change the story: her uncle was “incarcerated for his anatomically anomalous body[.]”

While Butler kept writing essays on “gender,” her 1984 dissertation – which she developed into a book published in 1987 – was on the French post-structuralist take on German Idealism. A harsh review by a senior academic may have hampered her efforts to find a conventional tenure-track philosophy gig. For whatever reason, she decided to combine her interests. In 1990 her smash hit, Gender Trouble, applied post-structuralist analysis to gender. She credited “Gayle Rubin’s extraordinary work” with inspiring her.

Butler’s prose is notoriously impenetrable. But she added a preface to Gender Trouble in 1999 that somewhat clearly conveys what she meant by it. I’ll rely on that and summaries of her thinking from the authoritative Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (SEP).

“Gender Trouble” (1990)

Gender Trouble’s big idea is that “performativity” creates gender. But it “is difficult to say precisely what performativity is,” Butler admits in 1999. “This text does not sufficiently explain performativity in terms of its social, psychic, corporeal, and temporal dimensions.” Her “theory sometimes waffles between understanding performativity as linguistic and casting it as theatrical.” But basically, doing, wearing, or saying stuff – perhaps any sort of stuff – is a “performance” of gender.

Butler does not define “gender.” She implies that it’s a term we all use to refer to a type of performance. “[W]hat we take to be an internal essence of gender is manufactured through a sustained set of acts, posited through the gendered stylization of the body.” Performance is what creates gender; gender is that which is performed.

Gender is not innate or an expression of something that is innate. SEP: “The expressive view Butler sought to replace presents gender as an inner self, which practices allow to emerge. By contrast, Butler saw those practices, and their repetition, as the source of gender.” Recently Butler reported her “‘gender identity’ – whatever that is – was delivered to [her] first by [her] family as well as a variety of school and medical authorities.”

This is anathema to trans ideology, which argues for medical treatment and civil rights based on a stable, innate “gender identity.” In fact Butler does not engage trans ideology. Other than a brief mention in the 1999 preface, it never utters “transgender” and refers to “transsexuals” only in passing. “Transvestites” (always the diciest term) don’t appear.

Butler knows she hasn’t defined gender. The first line of Trouble’s 1990 introduction: “Contemporary feminist debates over the meanings of gender lead time and again to a certain sense of trouble, as if the indeterminacy of gender might eventually culminate in the failure of feminism.” Neither the collapse of feminism nor the task of writing a book based on an unarticulated concept daunt Butler. “Perhaps trouble need not carry such a negative valence.”

If Butler doesn’t want feminism to fail, she seems to want it to … change. Chapter 1”reconsiders the status of ‘women’ as the subject of feminism[.]”

While Butler’s writing is numbingly opaque, she makes clear in interviews that gender is painful for her: “It was with some difficulty that I found a way of occupying the language used to define and defeat me.” In Trouble she often uses the word “violence” to describe social pressure (“the mundane violence performed by certain kinds of gender ideals”).

Are women real? “[T]his text does not answer the question of whether the materiality of the body is fully constructed[.]” Butler says she answered it after Trouble. But I don’t think she did. SEP in 2023: “Butler is not wedded to the idea that we need a stable conception of women. … [S]he asks whether “the construction of the category of women as a coherent and stable subject” is “an unwitting regulation and reification of gender relations.”

Sex has to be a construct in Butler’s view because she is a constructivist. If a woman’s body is inherently meaningful then her career is not. Once you’ve digested thousands of pages of French and German philosophy to write a dissertation on how there are no stable categories, you’ve got to knife any biologist who says “well actually people with disorders of sex development are all classifiable as male or female.”

What is the point of Gender Trouble? “[T]o open up the field of possibility for gender without dictating which kinds of possibilities ought to be realized.”

What’s the point of opening up gender possibilities? “[N]o one who has understood what it is to live in the social world as what is ‘impossible,’ illegible, unrealizable, unreal, and illegitimate is likely to pose that question.”

Trouble seeks “to undermine any and all efforts to wield a discourse of truth to delegitimate minority gendered and sexual practices.” It’s weird to shrink away from a “discourse of truth,” i.e., discussion based on logic and shared values, when what you’re defending is romance between adults of the same sex. Perhaps, like Rubin, that’s not what she wants to defend.

Butler seems to like drag. In 1990, she rejects “feminist theory’s” criticism of the “subversive” practice. “[P]art of the pleasure, the giddiness of the performance is in the recognition of a radical contingency in the relation between sex and gender …” But in 1999 she clarifies that this pleasure doesn’t mean anything:

“[T]he positive normative vision of this text, such as it is, does not and cannot take the form of a prescription: ‘subvert gender in the way that I say, and life will be good.’”

Butler believes “gaining recognition for one’s status as a sexual minority … [is] a necessity for survival.” What is recog–wait, literal survival? Let’s just move on.

Judith Butler, Team Player

People often assume Butler wants to achieve some sort of material win for women or gay people. This is a mistake.

In 1999, the philosopher Martha Nussbaum pilloried Butler for being a bad feminist whose writing doesn’t help “women who are hungry, illiterate, disenfranchised, beaten, raped[.]”

So? You could say the same for Hegel. Nussbaum gasps:

“She tells us … that we all eroticize the power structures that oppress us, and can thus find sexual pleasure only within their confines. It seems to be for that reason that she prefers the sexy acts of parodic subversion to any lasting material or institutional change.”

Well, yes, that’s at least what Butler wants you to think. Her mentor is Gayle Rubin, a woman who claims to be a sadist to bolster her credibility as a champion of pedophiles. In assaulting Butler’s “naively empty politics,” Nussbaum comes off as a bit naive herself.

Blake Smith similarly assumes Butler has humanitarian aims. Relating an episode where she lashed out at a young lesbian who spoofed her, Blake charges that Butler “oppressed the women and gay people Butler meant her work to help protect.”

Butler does not mean her work to protect women or gay people. She doesn’t even talk about women or gay people – those concepts are too “naturalized.” She prefers to expound upon “the incest taboo” and “the bisexuality that is said to be ‘outside’ the Symbolic.”

Notice those are abstractions, not people, and Butler doesn’t propose salves for the tragedy they imply. She can’t even say whether Trouble is “normative” or what the value of “opening possibilities of gender” is. She just wants to “gain recognition” for “sexual minorities” (a phrase she started using after 1990 when perhaps she realized her books needed characters) by having them “perform” in a way that isn’t innate to them, might provoke “violence,” and won’t reliably lead to a “good” life.

Recently Butler has embraced trans rights, asserting with relative lucidity that she is nonbinary (“I don’t see how I cannot be in that category”). She didn’t have trans on the brain when she wrote in 1990 about the importance of “gaining recognition.” But “pretend I’m not a woman” turned out to be the perfect prescription to cap off her vaporous philosophy.

It’s easy to imagine a world where Rubin and Butler remained obscure. After all, they were really just litigating internecine lesbian disputes. Rubin could have been cancelled by NAMBLA’s critics; Butler might have been hired by a small liberal arts college that needed a Germanist.

But that’s not what happened. Their careers took off and now they’re considered visionaries. Why?

In Part 2 of this essay I’ll show how straight people created a market for gay nihilism.

Further reading:

Ben Appel’s brilliant and funny new memoir, CIS WHITE GAY, goes deep on queer theory. He’s not a fan.

Rubin has since complained about conservatives “misconstruing” her words. But her support for “boy-lovers” is unqualified in Thinking Sex, so long as they act nice and secure consent. Nowhere does she differentiate between 17-year olds and 7-year olds, and she makes clear she’s talking about “cross-generational” sex rather than teen romances.

Brilliant as always, with many guffaw-worthy lines. Hard to pick just one but I especially liked "Once you’ve digested thousands of pages of French and German philosophy to write a dissertation on how there are no stable categories, you’ve got to knife any biologist who says “well actually people with disorders of sex development are all classifiable as male or female.”"

Fabulous & lucid review of two very obscurantist writers. I always tell my students to be wary of poor writing: it’s an almost certain tell that it’s hiding something.

I’ve come to think of Butler et al as like the COVID-19 lab leak: these were fun (if slightly stupid) ideas to play with in graduate seminars in the 1990s, but they weren’t fit to be let loose on the streets for the hoi polloi. But then: the internet, Tumblr, Twitter, & Reddit served these (still stupid!) ideas up to bright autistic adolescents.