Idaho Comes for the American Academy of Pediatrics

A 21-state probe is the first major investigation into gender fraud by American law enforcement

“It’s a great work of art like the statue of Venus, if you’re wearing a hat on the head of your penis.”

–Edgar J. Schoen, drafter of the AAP’s circumcision guidelines (1987)

Since October 2018, the influential American Academy of Pediatrics has advised that sex is assigned at birth, people are attracted to gender (not sex), and young children “know their gender.” It “recommends” that kids who say they’re trans receive “gender-affirming” interventions; that medical records “respect” gender identity (by stating the wrong sex?); and that pediatricians agitate for trans political goals.

This wisdom is contained in a “Policy Statement” drafted by Jason Rafferty, who was a young resident at the time. The sexologist James Cantor swiftly debunked it, showing that it misrepresented the papers it cited as authority. The AAP’s members have petitioned it to review the Policy Statement. But the AAP stands by it.

Since publishing the Policy Statement in 2018, the AAP has blundered through the gender wars like a freshman at the prom. Everyone from WPATH to Dame Hilary Cass has dissed it. Last year a detransitioner sued it for conspiring to deceive the public. In September, 21 states announced they were investigating the AAP for defrauding the public. That makes it the first gender prankster to be called to the principal’s office.

(Trans rights lawyers are under investigation by a federal court in Alabama, but not for lying about gender medicine. Missouri, Tennessee, and Texas have separately initiated investigations into local gender doctors.)

The AAP has not employed a lawyer in a top executive role during this period, as far as I can tell.

This post is about the AAP’s legal vulnerabilities.

What Is an Academy?

The AAP is a nonprofit headquartered near Chicago with about $173 million in assets and $129 million in annual revenue. It also has an office in DC. It boasts 67,000 members.

The AAP’s name is gold. It exploits this. Its corporate donation page asks, “Why partner with the AAP?” First answer: “We are trusted.” The AAP’s membership dues are $675 for attendings. The first selling point: the right to call yourself a fellow of the AAP. Some of these big spenders append “FAAP” to their name after MD.

In 2017, the AAP lent its credibility to the ACLU by filing a brief (with WPATH and others) in support of identity-based school bathrooms. Soon the rest of the dues-collecting, corporate-partnering medical world had joined the cause, including the AMA. They now regularly file joint amicus briefs drafted by major commercial law firms in pediatric gender medicine lawsuits. The AAP takes top billing – surely an optics play. Last month the gang filed an amicus brief with the US Supreme Court.

In April 2024, when the US Department of Education tried to re-write Title IX to let boys into girls’ locker rooms, it cited the AAP’s support of the idea as authority.

The AAP publishes pro-transition articles like the Policy Statement in its peer-reviewed journal, Pediatrics. It does not publish critiques of youth transition. In the words of Kris Kaliebe, a psychiatrist at the University of South Florida, this “formerly high-quality journal has been used to cheerlead for the ‘gender-affirming care’ scheme rather than to provide a forum for rigorous scholarly debate.” (Links in original.)

The AAP’s Leadership

Mark Del Monte became interim CEO of the AAP in July 2018, just a few months before it published the Policy Statement. Del Monte had been climbing the org’s ranks for over a decade handling comms, public relations, and “advocacy” (lobbying). He was soon named AAP’s first non-pediatrician CEO. Now his salary exceeds $783,000.

Del Monte graduated from UC Berkeley’s law school in 1997 and worked in HIV/AIDS advocacy, first as a legal aid lawyer in the Bay Area and then, in DC, as a policy guy. He’s now based at the AAP’s Illinois office.

Del Monte’s California law license is “inactive” and he is not licensed in DC or Illinois, according to my searches. He appends “JD” to his name. Licensed attorneys use “esq.,” if anything. Unlicensed JDs aren’t lawyers.

The AAP’s “leadership team” does not include a general counsel or any other esquires. Tax filings list its top 20 employees by salary — none of them hold legal titles. I found one AAP attorney on LinkedIn who says she was hired to the post in 2015. This woman claims her title is “Attorney,” which doesn’t sound like an official workplace designation. She shares a last name with someone who was the AAP’s associate executive director the year she was hired, earning over $360,000.

No one on the AAP’s board of directors appears to be a lawyer.

Of course, the AAP retains outside counsel to handle litigation. It may also retain outside counsel for day-to-day legal issues. Judging by older tax filings, it appears the model predates Del Monte.

Nonprofits don’t always need in-house lawyers, but big ones tend to maintain a General Counsel’s office. For comparison, the ACLU ($201M revenue, $786M assets)1, AMA ($447M/$1.16B), American Psychiatric Association ($64.9M/$169M), and American Psychological Association ($133M/$259M) have GCs; WPATH ($2.55M/$1.85M) and Endocrine Society ($28.5M/$75.8M) appear not to.

Why Lawyers Matter

It’s a good idea to include a lawyer in your org’s upper ranks because:

Lawyers handle ethics questions.

Lawyers protect assets from lawsuits.

Non-lawyers don’t always recognize when they’re dealing with an ethical issue or a problem that could turn into a lawsuit. A general counsel is a chaperone strolling around the C-suite.

When a company lawyer gives legal advice to colleagues, the conversation is privileged as attorney-client communication. When a “JD” CEO talks strategy with underlings, the conversation is not privileged.

Lawyers can also spot PR problems in the making. Perhaps the AAP had no lawyer in 2010 when its bioethics committee referred to one form of female genital mutilation as a “ritual nick” that “is no more of an alteration than ear piercing” for young girls. The world interpreted the mealy-mouthed FGM statement (which superseded a clear condemnation that AAP issued in 1998) as a tacit endorsement of some forms of the practice. Under fire, AAP soon withdrew it.

The Disclaimer (2018)

The Policy Statement includes a line at the bottom:

“Dr Rafferty conceptualized the statement, drafted the initial manuscript, reviewed and revised the manuscript, approved the final manuscript as submitted, and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work.”

This is unusual. Professional associations usually run docs like these through elaborate review processes. Confusingly, the AAP itself alludes to this just a few sentences later:

“Policy statements from the American Academy of Pediatrics benefit from expertise and resources of liaisons and internal (AAP) and external reviewers.”

Observers don’t know why the AAP credited Rafferty so ostentatiously. Critics have referred to the line as a disclaimer because it seems aimed at clearing the AAP of responsibility. But legally, it almost certainly does not do that (I’ll explain below). So what is going on?

Theories:

The Policy Statement lists the members of three committees without explaining what their relationship to the endeavor is. It seems to be a formality, perhaps indicating that a majority of each committee approved it. Maybe some FAAPs asked for the disclaimer because they knew their names would be attached to the Policy Statement and wanted to distance themselves however possible.

Rafferty is a credit hog. He demanded the disclaimer because he wanted the world to know the Policy Statement was all him. Maybe he was angling for copyright. Unfortunately, the disclaimer is followed by: “This document is copyrighted and is property of the American Academy of Pediatrics and its Board of Directors.”

The AAP was concerned about liability but did not consult a lawyer.

Since then pediatricians like Julia Mason, of Portland, Oregon, have beseeched the AAP to take another look at pediatric gender medicine. The AAP made some noises about a systematic review in 2023 but nothing has come of it. That same year, it “reaffirmed” the Policy Statement, apparently because otherwise it would have automatically expired.

This year the Cass Review found that the Policy Statement was among the worst-quality pediatric gender recommendations in the world.

The Yale Law School Integrity Project publishes articles in defense of pediatric gender medicine. Its takedown of the Cass Review puffs up authorities that conflict with Cass — except for the AAP Policy Statement, which it relegates to a footnote and erroneously refers to as a “Practice Statement.” The tone is grudging: “While not a guideline, the … Practice Statement … is often referenced by policymakers and the media. …”

AAP v. WPATH (2022)

WPATH released its Standards of Care version 8 (SOC8) in September 2022. In the run up, it let the AAP comment on the draft. WPATH viewed AAP as an annoying little brother, internal emails reveal. (The emails were exposed this year in the course of a lawsuit. I’m taking these anonymous quotes from Cantor’s expert report to the court.)

SOC8 drafters’ reactions to the FAAPs’ comments:

“I am seriously surprised that ‘reputable’ association as the AAP is so thin on scientific evidence.”

“I have also read all the comments from the AAP and struggle to find any sound evidence-based argument(s) underpinning these.”

“I was shocked to see the feedback from very junior people from AAP.”

“This is really a shame if the experts at AAP are junior and flexing to change another societies guidelines.”

Nonetheless, the AAP held sway. After it threatened to oppose SOC8 if it contained age minimums, WPATH caved. (The federal official Rachel Levine had also applied pressure.) WPATH considered the fracas “highly confidential.”

WPATH retained some measure of dignity: it did not cite the Policy Statement in SOC8.

Isabelle Ayala v. AAP (Oct. 2023)

In October 2023, a detransitioner named Isabelle Ayala sued the AAP, Rafferty, and others in Rhode Island state court for conspiracy to deceive the public through the Policy Statement. The case is ongoing.

This isn’t the first time the AAP has been sued for publishing unscientific medical guidance. In 2021, Shingo Lavine and his parents sued the AAP in New Jersey federal court for issuing guidelines in support of circumcising baby boys – Lavine’s own had been “botched.”

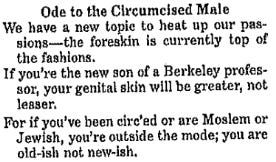

According to the complaint, in the 1970s the AAP took the position that circumcision was not medically necessary. Then in the 80s there were some lawsuits against circumcision doctors that roiled the field. A pediatric endocrinologist named Edgar J. Schoen, whose buddy had been sued, became a pro-circumcision activist. In 1987, Schoen published a sarcastic poem in a medical journal about parents who choose not to circumcise their sons:

In 1988 the AAP appointed Schoen to chair its Task Force on Circumcision. The next year it published new, stridently anti-foreskin guidelines in Pediatrics. Lavine argued they were fraudulent.

The court dismissed the suit. I won’t parse the opinion because it’s in a different jurisdiction than Ayala. I just want to highlight some of the factors the judge considered, and show how different the circumcision statement sounds from Rafferty’s.

The disputed parts of the circumcision statement are “tentative scientific conclusions or opinions, not statements of fact[.]” Lavine quotes terms like “tentative” and “preliminary data.” By contrast, Rafferty’s statement asserts that sex is assigned, sexual orientation is based on gender, and gender identity “result[s] from … biological traits” (false). This is all in his “definitions” table, which implies they are facts.

Lavine gives leeway to the AAP because:

“Articles in peer-reviewed medical journals are the modern equivalent of the public square; they are the forum where the debate about medical science occurs. Part of the debate occurs before publication, between the authors who submit an article and the external peer reviewers … And part of the debate occurs after publication …”

But Rafferty’s statement was all him and the AAP iced out the criticism that exploded after publication.

Lavine notes that the AAP doesn’t have “considerable influence.” In the gender context, though, the AAP has filed amicus briefs, engaged in advocacy, and pressured WPATH. It “recommends” that pediatricians wave the striped flag. If the AAP lacks considerable influence on transgender issues, it’s not for lack of trying.

A general counsel would have advised the AAP years ago to shield itself from fraud claims by clearly demarcating facts from opinion, engaging with criticism, and toning down the activism.

Please Bury Your Emails in the Backyard (Dec. 2023)

If you work for a public body, like a state university, members of the public are entitled to demand emails related to your work under the federal Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) and similar state laws. It doesn’t matter whether you used your “work email” account or your “personal” Gmail or some random burner – what matters is that the message relates to your work.

When an agency receives a FOIA request, its FOIA officer asks any employees who might have sent or received messages relevant to it (“custodians”) to aid the search for these messages so that the agency can fulfill its legal obligation. The custodians are supposed to turn over anything on point from their “personal” accounts. The agency can search the custodian’s “work email” without their cooperation.

A similar scenario plays out when an organization – any org, not just a public one – is investigated by the government, or embroiled in discovery during a lawsuit. If it receives lawful demands for employee emails, the employees must search their personal accounts for relevant messages.

In the real world, employees might not fork over messages from their “personal” account because they think they can get away with it. This is wrong. But only aggressive investigations will expose the misconduct.

In December 2023, the AAP issued a directive to its members in leadership positions. It said they should not use their work email accounts to discuss AAP business:

“Members do not ‘own’ their work email and so do not necessarily have decision-making authority about whether or not to release it publicly. The AAP must take this prudent step to enable communications to remain in the control of the AAP and its volunteer leaders, while preserving our vital history.”

AAP then cited “vulnerabilities” of employer platforms: the emails “are subject to the document retention and release policies of external institutions, including in response to subpoenas or [FOIA] requests.”

In other words, the “external institutions” might follow the law. The AAP wanted its leaders to “have decision-making authority” to obstruct investigations and defy lawful demands.

The AAP mis-advised that using personal accounts “enables you to retain full personal control and legal rights to your email communications on Academy issues …”

Since many orgs require that employees stick to their work email to discuss work matters, and professional committee work (like AAP stuff) often overlaps with day jobs, this directive likely set up ethical dilemmas for AAP members.

Some phrases in the directive were just odd. The “lack of privacy on employer-sponsored email platforms can create employment challenges.” Does this imply the AAP members could be fired over the contents of their AAP emails?

“The Academy must protect its intellectual property by ensuring that our member leaders can engage in robust discussion and debate …” IP refers to commercializing ideas. Is the AAP worried its members’ employers will steal ideas from them that the AAP wants to cash in on? (I think the answer is No, it’s just throwing random legal terms around.)

Overall, this directive makes the AAP look like it wants to hide evidence. That means investigators will approach it more aggressively – subpoenaing individuals instead of relying on centralized doc production; deposing many people.

Benjamin Ryan FOIA’d the emails of AAP leaders who worked for public institutions. He published his findings in September. They reveal a national FAAP meltdown over the AAP’s choice to hold a conference in Orlando (“I personally do not feel safe going to Florida as a visibly queer/genderqueer human”), among other goofiness. Ryan writes that he would not have thought to FOIA the emails if not for the AAP’s personal-email directive.

Since Ryan has not uncovered damning evidence of fraud, I wonder if the AAP was just nervous about the public reading emails that accused it of transphobia and insufficient hatred of Ron DeSantis.

I think a lawyer would have advised against issuing the personal-email directive.

The Cops Show Up (Sept. 2024)

In the past I’ve questioned whether the Republican party is serious about fighting the gender industry. Now I think many of its state officials are.

In September Raul Labrador, the Attorney General of Idaho, publicized a letter he had just sent to the AAP demanding documents and explanations related to its gender recommendations. Elected officials in twenty other conservative-leaning states signed on.

The Law

The states are investigating the AAP under their consumer protection laws. Generally known as UDAP statutes, for “unfair and deceptive acts and practices,” they vary slightly by jurisdiction. They’re all practical, flexible standards.

Courts look at what the defendant did and consider whether it would trick a regular person. A fraudster can’t wriggle out of liability by sticking some fine-print magic words in a footnote somewhere. Or by inserting a disclaimer that it’s all Jason Rafferty’s fault.

The Players

It’s common for states to band together when investigating UDAP violations. The advantage of “multistate” investigations is they have manpower and leverage; the downside is they tend to lumber. It’s not easy getting 21 bureaucracies to agree, or to respond to emails asking whether they agree.

Consumer protection is popular across party lines – voters of both parties hate being cheated – so liberal and conservative AG offices often collaborate. The attorneys know and like each other. But no Democratic AGs have joined Idaho. (Arizona signed on through its legislative leaders, not its Democrat AG.)

Some Republican AGs did not sign the letter: Alaska, Indiana, Kentucky, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Wyoming.

The Investigation

The letter starts by laying out the AAP’s misconduct. It covers broad territory but zeroes in on the Policy Statement’s claim that puberty blockers are “reversible”:

“That statement is misleading and deceptive. It is beyond medical debate that puberty blockers are not fully reversible but instead come with serious long-term consequences.”

The Policy Statement does concede in a footnote that “reversibility is based on the little data that are currently available.” I don’t think that’s enough to save the AAP. In fact, it shows the AAP knows its claim is shaky — a fact that can lead to higher penalties.

Idaho quotes the Cass Review to make an interesting point:

“Puberty blockers block normal pubertal experience and experimentation, and thus there is ‘no way of knowing whether the normal trajectory of the sexual and gender identity may be permanently altered’ by blockers[.]”

This is an allusion to studies showing most gender-nonconforming kids grow up to be gay.

Let that sink in: Republican politicians are referring to “experimentation” as “normal” and suggesting it’s wrong to interfere with children’s natural development into gay adults. Meanwhile, Democratic AGs keep filing amicus briefs in support of stunting the sexual maturity of gender-nonconforming kids.

The letter makes fourteen demands. In some cases I don’t know what they’re getting at but I look forward to finding out:

“Explain efforts by the AAP to incorporate its recommendations (including the 2018 AAP policy statement) into patient care by any doctors or medical providers, including through ‘smart phrases’ or other systems that automatically incorporate medical standards.”

“Provide a copy of all communications, both internal and to third parties, that you have had between March 1, 2024, and the present regarding the SOC8, including any discussion related to pages on your website referencing WPATH and/or the SOC8.”

Next Steps

The letter’s deadline was October 8. It’s likely the AAP negotiated a deadline extension for at least some of the demands.

If the AAP doesn’t cooperate then Idaho – or any state – can escalate by issuing “civil investigative demands” or a subpoena (states use different terminology). Then the AAP could sue to quash the demands, and the issuing state could sue to compel compliance. I think a judge is likely to compel compliance. Idaho has demonstrated a factual basis for suspecting UDAP violations and doesn’t seem to be hassling the AAP on a lark.

AGs don’t need to prove injury under at least some state UDAP laws, meaning they could win penalties based on false statements alone. The penalties should be enhanced because the AAP didn’t mislead the public about blockers by accident – its leadership is a bunch of distinguished FAAPs who should have known better. If the AGs can establish that the Policy Statement or other AAP gender shenanigans harmed kids then courts may order the AAP to pay restitution. (Don’t get your hopes up.)

As investigators get behind the scenes of the AAP, they might find misconduct they hadn’t anticipated. After all, it seems the AAP has been operating in a clumsy way and its strategic communications will not be protected by privilege if they did not involve a lawyer.

I can picture depositions being fruitful. The FAAPs are less slick than their big brothers at WPATH, who dazzle judges on the expert witness circuit, pal around with “social justice lawyers,” and visit Disney World without a bulletproof vest.

Like the Lavine (circumcision) court, judges reviewing the states’ lawsuits might ask themselves if they really want to referee scientific discourse. But here, they should conclude that the Policy Statement is not scientific discourse.

The AAP doesn’t feature LGBTQ issues on its “advocacy” page, which shields much of its content behind log-in screens.

But the AAP does focus resources on trans. In an email unearthed by Ryan, the FAAP Christopher Bolling gushed about how the AAP supported his trans activism:

“It’s almost impossible to state all the ways they helped. Their state and legislative affairs team responded within hours if not minutes when we had obnoxious amendments submitted in KY and OH, they empowered our very active state chapters with advice, they helped us draft letters, they taught us how to sign on to amicus briefs with ACLU to federal courts, etc.”

The AAP invested so much effort in influencing the law — and so little in following it.

That’s just the ACLU’s 501(c)(3) nonprofit. Its 501(c)(4) — which can explicitly campaign for candidates and causes — and local affiliates are separate legal entities.

This entire piece is fascinating, but this paragraph in particular jumped out at me, especially given US v. Skrmetti, which is very much on my mind at the moment: "If trans activists had not sued red states for protecting minors from gender medicine, I think it’s unlikely the AGs would now be investigating the AAP. After all, the AAP’s recommendations about puberty blockers would be null and void in their states thanks to the bans."

I'm going to stitch a few quotations together to make a point. The first two are taken from this piece.

"Since October 2018, the influential American Academy of Pediatrics has advised that sex is assigned at birth, people are attracted to gender (not sex), and young children 'know their gender.' It 'recommends' that kids who say they’re trans receive 'gender-affirming' interventions; that medical records 'respect' gender identity (by stating the wrong sex?); and that pediatricians agitate for trans political goals."

The AGs have asked the AAP to:

“Explain efforts by the AAP to incorporate its recommendations (including the 2018 AAP policy statement) into patient care by any doctors or medical providers, including through ‘smart phrases’ or other systems that automatically incorporate medical standards.”

The final quotation requires some explanation. I recently discovered that my medical records at two of my health care organizations give my "sex assigned at birth" and my "gender identity." I objected.

To say my sex was assigned at birth is neither factually nor scientifically correct. When I was born almost 70 years ago in South America, the notion that sex is assigned at birth in the Queer sense of the term had yet to be summoned from the void by Queer Theory philosophers. I'm trapped in an anachronism. Scientifically speaking, my sex was determined biologically at conception and, since my physiology is not ambiguous, observed and recorded by the physician who delivered me.

As for gender identity, I explained that I do not have one. I do not "identify as" a male. I AM male.

Lastly, I said that sex assigned at birth and gender identity are rooted in philosophy and activism, not science, and have no place in medicine.

I asked that the organizations correct the errors in my medical records.

That brings me to the reply I received a while ago from the manager of compliance, risk and quality for one of the organizations:

"Thank you for bringing your concerns to our attention. The sex assigned at birth and gender identity fields are fixed fields in the medical record. Thus, the information cannot be removed. However, you are welcome to select the "Choose not to disclose" option if you do not wish to select an answer. Sex assigned at birth is the recognized nomenclature in health care. This is also the nomenclature used by the CDC. As you mentioned, the sex that is assigned by a medical provider is based on the genitalia (and in certain cases other factors) observed at birth."

"We appreciate your feedback regarding gender identity, but as an organization that is proud to serve a diverse population of patients, we believe that it is important to give all patients the opportunity to express their identity and have that identity acknowledged. Please feel free to select the "Choose not to disclose" option if you do not wish to provide an answer for the gender identity field."

The positions she expresses clearly reflect efforts on the part of an unknown actor to incorporate its multifaceted positions on gender into patient care. Was it the AAP? The identity of the activist doesn't matter as much as the fact that those pernicious concepts have metastasized and become lodged in nooks and crannies throughout the American health care system.

Neither of the suggested solutions is satisfactory.

The last thing I want to do is create potentially dangerous uncertainty in my medical record about something as basic and vital as my biological sex by opting for "Choose not to Disclose."

With respect to the “Gender Identity” box, selecting "Choose not to Disclose" would be no improvement. I would still be conceding that I have a gender identity. The point is that I do not.

The only satisfactory option is to let me select “none” under the gender identity heading. Otherwise it would be like asking for a patient’s religion and not allowing patients to select “none.” (The clinic does give patients the option of choosing "None" in the religion category. ) Since gender ideology is more like a religion than a science, the very least The Portland Clinic could do is give me the same choice with respect to gender identity.

I have been wrestling with how to characterize the compliance manager's rhetoric. It was only when I read a recent essay by the British author and cultural writer Helen Pluckrose that I found a passage that describes it perfectly. The health care organizations are:

"conflating sexuality with gender and gender with sex, “educating' everybody in their own theories, policing language, making people affirm things they don’t believe and trying to shoehorn issues of sexuality and gender into absolutely everything even when it has no relevance at all."[1]

Alone, I stand no chance of purging the genderist terminology that has embedded itself in my medical records and those of the organizations' other patients. It's indisputable that it needs to go. Since the errors reside in the same third-party provider's patient interface (MyChart), they are systemic and very likely affect patients in many states. Maybe I should drop the Idaho AG a line.

In closing, in addition to having been general counsel for financial services business before I retired, I have also been a compliance manager and a compliance officer. Among other things, I practiced preventive consumer law. The health care organization's response makes me grateful that when I was in the compliance field I never had to be an advocate for unscientific concepts or thwart a customer's reasonable request with specious arguments. I do not know whether either of the organizations have a gender medicine practice. I do know that I would have many sleepless nights if I were the risk manager for a trans chop shop.

[1] Pluckrose, Helen. “Why Do You Need to Talk About Sexuality at All?” The Overflowings of a Liberal Brain. 8 September 2024. https://substack.com/@helenpluckrose/p-148622634